Enric Farrés Duran

El Viatge Frustrat (The Frustrated Journey), 2015-2016

Video | Colour | Sound | 1 hour 45 minutes

El Viatge Frustrat/The Frustrated Journey is an art project by Enric Farrés Duran, produced by Cal Cego, in which the artist and the collector embark on an adventure at sea, with the idea of recreating the voyage to France made by the writer Josep Pla and his friend Sebastià Puig i Barceló—better known as Hermós—in 1918. In the story ‘Un viatge frustrat’ (first published in Un bodegó amb peixos, Selecta, 1950), Pla recounts in considerable detail the voyage, using sail and oars and without passports, and the ostensible reason for making it: to visit some relatives of Hermós in Roussillon; however, in the course of the journey the underlying motivation is revealed as being to get home again to tell the story. As we know, Pla never made the frustrated trip, which fits into the idea of creating fictions incrusted with a wealth of authentic details (real persons, types of fish, weather conditions, moods and so on) to give them veracity.

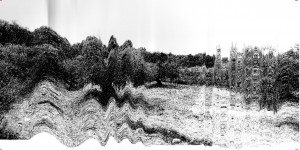

Unlike Pla, Farrés Duran actually made the frustrated voyage, setting out from the Costa Brava in the month of August 2015. What is more, his intention was to create not a realist fiction but a fictionalized reality on the basis of specific documentation which is closer to holiday photographs and videos than to the epic and tragic tradition so often associated with projects related to the sea by artists and filmmakers (we might think here of Bas Jan Ader’s In Search of the Miraculous or Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog, to cite a couple of examples).

The Frustrated Journey of Enric Farrés Duran is the opposite of heroic: an artist is towed in his tiny boat (a two-metre wooden barge, motorless as the result of a mysterious theft) by another, perfectly seaworthy vessel (a replica of the poet and publisher Carlos Barral’s boat, named ‘Captain Argüello’ but popularly known as ‘La Barrala’) skippered by the art collector Josep Inglada, one of the people behind Cal Cego. During the trip there are difficult moments and periods of leisure, waiting and chance encounters.

In The Frustrated Journey everyday life occupies almost all of the footage, which is filled with time spent waiting, time in which nothing out of the ordinary happens. There are no stories of love or hatred, robbery or murder, there is no mystery and no amazing coincidences, but the fact that nothing happens and yet expectations are created also deserves some explanation, and, as the voice-over tells us at one point in the video: ‘Appearances do not deceive, they are appearances.’ In the light of this, Farrés Duran’s points of reference are to be found in writers like W. G. Sebald and Enrique Vila-Matas or artists like Ignasi Aballí and a whole genealogy of ‘No artists’ who, like Bartleby, disappear, stop writing, stop making nothing the object of their work to approach reality from new perspectives.

Time is another key theme, with vacation time and production time mixing and merging, like the time on shore in which nothing happens, waiting for better weather conditions to make the trip.

In a very ordinary, everyday way the video addresses some of the major themes of art, such as the relationship between artist and collector, the decision to let oneself be carried along or to take the helm and, to some extent, the debunking and revising of roles: the artist is no longer heroic — he devotes part of his working time to stretching out in the small boat and posting on Facebook — and the collector is no longer the patron who purchases the work, or produces it by providing the funds needed to being it to fruition, but the person who provisions and sails the boat and does the cooking. Another aspect of this is the journey towards internationalization (quite clearly shown here as a naive position), which is so important if an artist’s work is to be recognized and legitimated.

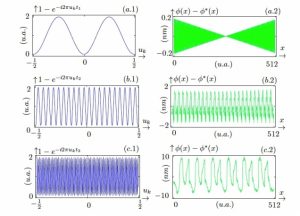

In The Frustrated Journey the script is being written as it happens. The video — a format that Enric Farrés Duran explores for the first time with this work, which has been edited by Telma Llos Martí — makes use of resources reminiscent of YouTube tutorials or Skype video conferencing; we are shown Google Maps, archive material and the artist’s own computer desktop. In this way, using video treatments and present-day communication formats, Enric succeeds in translating to video the use of the first-person narrative that, in other projects, has taken the form of a book or a guided tour.

Montse Badia